There’s a recent opinion article over on Glenn Beck’s platform “The Blaze” that takes issue with Bandit Heeler, the dad from the wildly popular children’s show, Bluey.

When I say “popular” I mean “phenomenon.” Bluey accounts for over 25% of total streaming hours on Disney Plus. Take that, Marvel.

If you haven’t seen the show, that’s ok. It captures everyday episodes in the Heeler family of Australia. There’s Bandit the dad, his wife and mum Chili, and their two kids, Bluey and Bingo. Bandit has become a relatable and even aspirational character for dads today. I shed good tears when the creators dropped an episode that offers a subtle but powerful statement on men’s mental health struggles.

The issue, according to the opinion author on Blaze, is that Bandit is “unbiblical.” The piece accuses Bluey of inverting “biblical” gender roles by presenting Bandit more like a caring mother. (A conclusion the author came to after a brief conversation and three minute YouTube clip) I’ll leave it to you to decide whether this is click bait or not. I found the piece mostly clear and level headed, minus the claim that naming a female dog “Bluey” is an attempt at subverting gender by departing from gender stereotyped colors. (Come on now.)

Before we go any further; the one stipulation I gave myself for writing this brief piece is that I would not make it about defending Bluey the show. (As much as my opinions on the matter are strong ones)

No, the reason I’m clacking keys on my keyboard is because there’s a theological move at work in this piece that is incredibly common in conservative religious commentary and presently underwriting Christian nationalism but rarely discussed beyond the walls of the academy.

And that is “natural theology.” Natural theology fuels Christian nationalist policy and generates the popular concepts among conservatives like “hierarchy” or “patriarchy” or “gender roles” or “creation order”— natural theology encompasses them all.

(Seriously, start paying attention to how much “creation order” flies around. Once you see it, you can’t unsee it. And here’s a quick primer on why I find it both theologically problematic and dangerous)

In its most crude form, natural theology reads the physical world as a site of revelation. It is more than saying, “the heavens declare the glory of God” as the Psalmist writes. Natural theology derives morality and ethics from the way things are (or appear).

When it comes to Christian nationalism, this is the one area where I think we really need public theologians to be, well, theologians. We need sociologists to capture Christian nationalism in real time. We need psychologists to help us understand the levers of conspiratorial thinking. But we need theologians, too.

As you might expect, the headwaters for natural theology is Genesis. Or more accurately, a certain reading of Genesis. The book, according to the lens of natural theology, teaches “creation order”— an idyllic and ordered world before sin that serves as the clear template for God’s design, to which we must return.

There are a few problems with this approach.

The primary problem for natural theology is the way many of its popular, common iterations are quick to invoke seemingly objective “concepts” and “orders” and “mandates” which are “obvious” and “clear” in the biblical text.

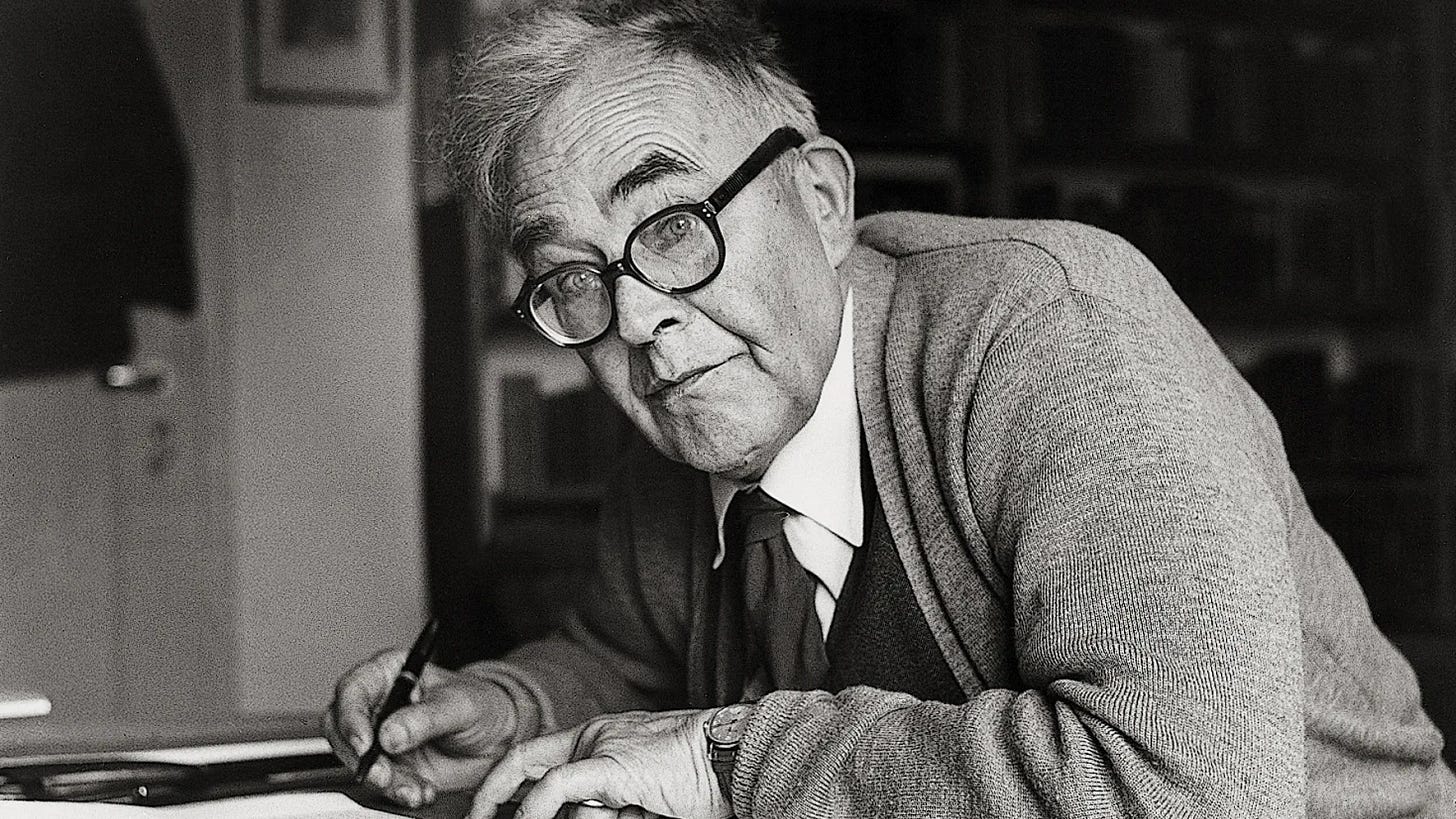

is helpful here noting that what gets labeled “obvious” is often signaling a host of unexamined assumptions. (Thanks to for sharing this)And then there’s Stanely Hauerwas who goes on criticizing this theological cargo when he observes, “the deepest and most painful divisions afflicting the church are those based on class, race, and nationality that we have sinfully accepted as written into the nature of things.”

Natural theology speaks so loudly and confidently on what is “normal” or “natural” that it risks relegating the central Christian confession, Jesus is Lord, to a secondary status.

When we hear more about conformity to “God’s design” than we do the liberating subversion of God’s reign, we are entering the realm of natural theology. Now, to this charge, proponents of natural theology offer the slogan “grace restores nature!” But this invites a second question: what is “natural”?

The challenge for the adherent of natural theology is providing an account for the natural. Many accounts assume a level of access into the intentions of the Genesis narrative that simply is not on offer. More often, however, is the mere imposition of cultural norms onto the text, reading them in such a way that uses Scripture to reify the status quo be it patriarchy or racial hierarchy.

It was not too long ago that what was “natural” and therefore “biblical” in American society included the denial of political representation to women, the segregation of races, the eradication of Native American populations, and the enslavement of Africans. The list goes on. Bandit has fallen under the same charge: his symbolic depiction is not “natural” — and by natural, the author means “aligns with creation order.”

My point in this quick two step primer is simply that natural theology risks relegating the revelation of Christ to a mere counterpart alongside and even subservient to whatever cultural norm appears most “obvious” to the majority and most at risk of deviation.

Natural theology can only say so much. It can really on ever insist that we go back to “creation order” which often ends up looking suspiciously like some nostalgic status quo a generation prior. In other words, natural theology can only ever see one set of problems: the lack of conformity to its vision of creation order, and so it surfaces these problems everywhere and in everything. Nothing is off limits.

We see this in how the article describes the father figure. Bandit Heeler symbolically “embodies almost all of the elements of the traditional mother, purged of the essence of elements from the historic faith” (emphasis mine)

Keep in mind: words like “tradition” and “historic” are load bearing. They can refer to the status quo, to ethnicentrism, to a national heritage, to a biblical reading. All of which are also incredibly arbitrary.

More to the point, concepts of masculinity are nowhere an essential element of the Christian faith delivered to and confessed by the saints. Who adjudicates what is traditional and historic? In a Protestant evangelical Christianity, the matter is only settled by endless claims to authority that awaits final judgment.

Going back to the article. The positive solution on offer is that, instead of Bandit, the author would have us look to Abraham as the “meta” symbol of fatherhood and masculinity. And I want to point out here how arbitrary this is. Why not Noah? Or Moses? Or Adam? The author has his reasons. I don’t find them convincing.

Because many attempts to construct a “creation order” under the premises of a natural theology end up having to impose its own hermeneutic horizon on Genesis and the Scripture writ-large. Invariably, this horizon forces an evacuation of the Christian Scripture’s witness to Jesus as the criterion and orienting object of Christian confession.

We do not confess creation order, but Jesus Christ.

The Bandit article laments a “lack of a symbolic depiction of fatherhood” in Western culture (another backstop for natural theology, by the way) which “has untethered the concept of fatherhood and masculinity from anything objective and leaves us vulnerable to following the ever-changing depictions of fatherhood and masculinity invented by modern cultural sensibili.”

I do not think it is a faithful reading of Genesis to identify Adam, Abram, Jacob, Isaac, or any other Biblical character, as a paragon of fatherhood and masculinity. That’s just not an agenda the text takes up in its recounting of Israel’s adventurous encounters and journeying with the God Who Saves.

The quest for something “objective” to serve as the backstop for a “biblical” masculinity ends up being paradoxically more conceptual and abstract in the hands of natural theology. It calls us to principles and arbitrary concepts that promise certainty but destroy the singularity of God’s revelation, the revelation given a witness by the community of Israel of the God who enters history, who acts, who suffers alongside and is faithful to his people.

Probably the most notable takedown of natural theology of the last century was offered by theologian Karl Barth who contended with the form of natural theology that allied itself with German National Socialism.

To this, Barth wrote: “The German Christians assert that next to Holy Scripture…the German nation (its history and its contemporary politics) constitute a second source of revelation, thus revealing that they believe in another god.”

Swap out “German nation” for “white America” and you see how the most crude forms of natural theology are making inroads among elements of American Christianity. There are theologians doing work in this area that I admire, and who recognize the risks of natural theology. But the natural theology which is proving most dangerous and immediate is not flowing from the academy, but from a reactionary conservatism that finds in natural theology the confidence and certainty which it so earnestly desires, but at too great a cost.

Natural theology fuels Christian nationalism by baptizing the status quo as normative. Behind the slogan, “make America great again” is a natural theology underwriting an arbitrary vision of order.

There’s more to say here about the outsized role natural theology plays in organizing Christian nationalism. Natural theology provides much of the backstop for a certain sort of Christian ethics, the kind that demands conformity to a conservative vision aimed at the realization of “creation order.” Our word for ethics originated from the word used for animal stalls. Conceptually, ethics concerns the stability for moral action. And “creation order” is for many an attractive ground of stability. Though it often refuses any or all criticism of the concept on grounds of being “unbiblical.” But there is more than one way to take the Scripture seriously.

I want to say, over and over again, not all Christian ethics agree, and even still, I hope each remain in conversation. This is good for the academy and church, together. But the Christian ethics that emerges from natural theology and maintains conformity to “creation order” is going to conceive of Christian life and witness in ways markedly contrasted to a Christian ethics that upholds the preaching of the Word and the practices of worship as the living encounter with God’s command.

I’m not a zealous worshipper of progress. But I’m not a reactionary, either. I think the Christian faith is quite unsettling and subversive on both accounts. The faith denies us much of the stability we might seek in conceptual “orders” and rather invites us onto the void and into the venture of God’s coming kingdom. The faith beckons us forward to resurrection while giving witness to a God who entered history and took up our cause. In suffering, Christ became our brother, made us his own, and invites us to pray “Our Father.”

So watch Bluey, enjoy Bandit. Be ever critical of natural theology and its promises of certainty that rest in the arbitrary.

As someone who likewise believes the theological unpacking of Bluey is the most important work the 21st century church can do, this is such an excellent addition to that discourse.

It's also helping me process some other feelings that I haven't really had language for. I recently re-read JD Vance's article in The Lamp and kept asking myself, "Okay, how did you go from this to...whatever the hell it is you're doing now?"

And I think you've given me the key I needed to think about it. This emphasis on the "order" of things, rather than on Christ's subversion of human orders. There's a pretty bog standard way of interpreting the Gospel as "getting back to God's way of doing things," and that produces a very different ethic than if you're starting from, "Jesus is God's condemnation of our way of doing things." Even then, it's easy to assume that if God is condemning the "ways of the world," then what God must be asking is that we replace those ways with a divine order.

... Except that's not at all what Christ proclaims. It's not at all what is meant by, "I desire mercy and not sacrifice." There is no "order" which infallibly conforms the heart to that of Christ. And to insist that there is means refusing to risk oneself, to undergo the terrible roller coaster of being truly sanctified.

Of becoming, perhaps, the sort of man who needs to be taught by their 6-year-old how to process their feelings and throw them into the ocean.

Thank you again for this. I'm glad I saw this at exactly the right time.

Just as a further complication- firstly Bluey is short for blue heeler, the Australian cattle dog, clearly. But. Australian vernacular calls redheads Bluey, because the Celtic redhead was considered “fighty “ and a fight in Australia is called a blue!

AND Blueys sister is a red heeler, as is the mother. Phew. So the family have married “out of class” so to speak.

Phew.